What if the Güran family really is innocent?

Not so long ago, only five months back, the murder of Narin Güran was one of the topics most dwelled upon by newspapers, news sites, and television channels. Not only journalists, even those speaking on daytime TV shows had turned into detectives.

The village of Tavşantepe in Diyarbakır had turned into a TV studio; instead of reporting concrete findings, some journalists entered a ratings race by conveying rumors and their own judgments. The predominant view in the media, which poisoned and influenced the judicial process, was that mother Yüksel, older brother Enes, and uncle Salim Güran had committed this murder.

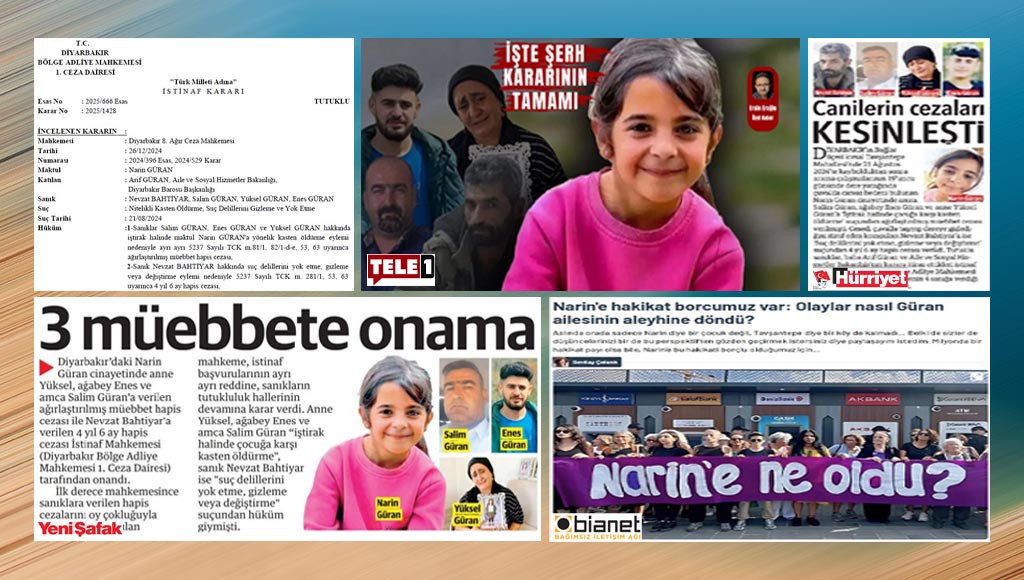

Indeed, the court also ruled in line with the expectations of the public opinion created by the media; family members Yüksel, Enes, and Salim Güran were sentenced to aggravated life imprisonment for the crime of murder, while Nevzat Bahtiyar was sentenced to 4 years and 6 months in prison for the crime of “destroying, concealing or altering evidence of a crime.”

Unfortunately, not only was this decision of the Diyarbakır 8th High Criminal Court insufficiently questioned in the media, but journalists also stepped aside with the comfort of having completed their duties. They showed little interest in last week’s appellate decision affirming the verdict and passed over it with small news items.

Yet the 1st Criminal Chamber of the Regional Court of Appeal had reached its decision by majority vote, and the president of the panel had attached a detailed dissenting opinion. In most media outlets, including AA, AHaber, Akşam, Cumhuriyet, Halktv, Ekoltv, Hürriyet, CNNTürk, İHA, Sabah, Sözcü, Nefes, Türkiye, and Yeni Şafak, this information appeared only between the lines.

Among the newspapers, only Milliyet printed the presiding judge’s dissenting opinion in a separate box. As far as I have seen, only Tele1[2]’s news site published the full text of the dissent, which was reported in detail by DHA[1] and Serbestiyet.

It is apparent that the President wrote the dissenting opinion, which is longer than the text of the judgment, after carefully examining all the evidence, statements, and reports in the file. The first point that caught my attention in the dissent was his emphasis that, “According to the new situation that emerged after the news and debates in social media and TV bulletins,” there were changes in the defendants’ statements. The President had clearly observed in the statements the influence of the media on the trial.

The President lists one by one the legal shortcomings in the investigation and trial, the contradictions between the reports, the ancillary evidentiary nature of the narrowed base station reports, the failure to determine the motive and manner of the murder, and the deficiencies and errors in the conviction.

After examining the dissenting opinion[2] published on Tele1 under the byline of Ersin Eroğlu, I recalled the concern I had felt during the process that began with the disappearance of Narin Güran. What if all or some members of the Güran family are innocent? What if we journalists also negatively influenced the judiciary and led to innocent people being convicted? These questions pained my conscience…

In fact, I had already fallen into the same concern about the court’s decision after reading DEM MP and communication scholar Sevilay Çelenk’s article published on Bianet, “We owe Narin the truth: How did events turn against the Güran family?” article and then her interview[3] with Gökçer Tahincioğlu on T24, as well as Esra Arsan’s piece “From earthquake reporting to the murder of Narin Güran, the exposed state of a journalism: The Ferit Demir legend (!)”[4] and the interview[5] in which Ferit Demir responds to the criticisms. These texts also contained striking observations that members of the Güran family might be innocent and about the media’s mistakes.

Now, to the questions raised in those articles have been added the legal objections emphasized in the dissenting opinion in the appellate process. The necessity has arisen to reopen this file, to examine it with journalistic cool-headedness, to pursue the evidence. If even one of those convicted, with our contribution as well, is innocent, this is a huge responsibility, a heavy burden on the conscience…

Mind-reading based on abstract assumptions

The President of the 1st Criminal Chamber of the Diyarbakır Regional Court of Appeal begins his dissenting opinion by emphasizing the principles of “presumption of innocence” and “in dubio pro reo” (“the benefit of the doubt goes to the defendant”). Most importantly, he concludes regarding the court’s conviction decision that “without expressing a conclusion based on the evidence in the file, the conclusion and reasoning reached in the form of mind-reading based on abstract assumptions is unlawful.” Without looking at whether it would be in favor of or against the defendants, he lists, one by one and in careful language, all the legal issues he has identified in the court’s decision; moreover, the appellate decision approved by the other two judges does not contain answers to the President’s objections.

The President’s 16-page dissenting opinion, which includes the view that the court’s decision should be overturned “for the reasons identified as being unlawful in terms of incomplete examination, legal qualification of the offense, proof, occurrence and acceptance,” will significantly ease the work of the panel that will examine the file at the Court of Cassation stage. The sections summarized from the dissenting opinion below show that the judge is trying to conduct a cool-headed legal assessment by stepping outside the influence of the media:

- It was not taken into consideration that there are contradictions between the narrowed base station report and the farm camera footage, which constitutes conclusive material evidence, and Nevzat’s statements regarding the occurrence.

- As it is seen that in both reports (Prof. Labudde and Ulusal Kriminal) sufficient enhancement could not be achieved and that there are contradictions between the two reports regarding the dark figure resembling Narin, I am of the opinion that it is not possible to render a decision based on these two reports.

- It is unlawful to render a conviction against Nevzat for the offense of concealing evidence of a crime, on the basis of the narrowed base station report, which contradicts the occurrence and concrete evidence and needs to be supported by other evidence, and his contradictory statements, while accepting that the act of killing is not proven with respect to him.

- Considering the existing state of evidence regarding Yüksel and Enes, it is necessary to assess in what manner their participation in the alleged offense occurred and what the legal classification of the offense should be.

- It is not established that there was a prior criminal decision taken concerning the killing of Narin before the incident.

- With respect to what the real purpose was for killing Narin, which is more important than the relationship between Yüksel and Salim becoming known, no conclusion has been expressed within the scope of the evidence; the conclusion and reasoning reached in the form of mind-reading based on abstract assumptions is unlawful.

- Considering Nevzat’s statements that he received Narin’s lifeless body from Salim, it is unlawful that the question of whether the act of killing directed at Narin was carried out personally by Salim was not discussed in the reasoned judgment.

- It is unlawful that, as a result of incomplete examination and by attributing the quality of conclusive material evidence to the narrowed base station report, which can only be accepted as ancillary evidence and does not allow for judicial review, the acts of Yüksel and Enes were deemed proven and judgment was rendered accordingly.

- Apart from Nevzat’s allegation that “Salim Güran told me ‘I killed this girl because she saw that we were together with Yüksel’”, no concrete evidence has been presented regarding these claims.

- It is unlawful that a decision was rendered without considering, within the scope of concrete material evidence, whether the crime scene was the driver’s seat of the vehicle used by Salim and whether the act of killing was carried out personally by Salim alone.

- It is understood that, during the hearings, attempts were made to obtain the witness’s knowledge regarding matters not acquired through the five senses, and that the court panel, counsel, and attorneys acted contrary to the Code of Criminal Procedure (CMK) by asking questions containing commentary that would not contribute to revealing the material truth, without complying with the rules of cross-examination.

The abuse case in Beylikdüzü

I do not know whether you remember the news report “Allegation of abuse of a 2-year-old child in Beylikdüzü”; the judicial process regarding the murder of Narin Güran and, most recently, the appellate decision reminded me of that incident.

That report, published on Bianet about three years ago, was based on a doctor’s account, a hospital report, and the fact that the Büyükçekmece Chief Public Prosecutor’s Office had launched an investigation. But later, the Forensic Medicine report did not confirm the allegation of sexual abuse; the investigation was closed.

When examining the report amid the ensuing debates, I had stated that the hospital report could not be disregarded and that, with the data at hand, the “newsworthiness of the allegation” arose, but I had also considered it a shortcoming that the family had not been interviewed. I had written that it was not the report but the allegation that had turned out to be wrong.

Later on, I thought a great deal about this assessment. Over time, I came to the conclusion that I had not sufficiently taken into account the pain of the family subjected to such a serious accusation. Until the allegation was clarified, the family members were subjected to an accusation of sexual abuse; they could not even experience the grief of their deceased child. Now, when I think of their situation, my heart aches.

The lesson I have drawn is this: following up on an allegation of sexual abuse – especially if it is directed at a child – is important, but it is also important to obtain the views of all parties, to use careful language, and to respect the family’s grief.

In the murder of Narin Güran, if even one of the family members is innocent and we, as journalists, have caused that innocent person to be convicted, this would be an unforgivable journalistic offense. We are faced with a duty to find answers to the questions left in the dark, to ensure that the legal problems in the case are resolved, and that the murder is fully clarified in all its aspects.

External References (5)